A small regional city of around 34,000 people, three hours drive southwest of Melbourne, the town of Warrnambool was founded in 1847; but its history stretches back far beyond its establishment as a European settlement. Studies of shell middens and fireplaces at the Moyjil/Point Ritchie headland at the eastern edge of the city indicate that the members of the Peek Woorroong people occupied the area around Warrnambool at least 35,000 and possibly as many as 80,000 years ago.[1] The area provided rich fishing and hunting grounds both on land and at sea.[2]

The first Europeans visited the area in 1802, when French explorer Nicholas Baudin sailed past on the French expedition to map the Australian coastline. The same wealth of natural resources in the area that had sustained the Indigenous inhabitants soon attracted European sealers and whalers during the early decades of the nineteenth century. And, later, from the mid 1830s, settlers who saw ample prospects in the rich volcanic soil of the region began farming of cattle. First surveyed and its grid pattern drawn up in 1846, the land sales of July 1847 marked the official beginning of the European town and one year later there were already fifteen houses.

At the same time, there were an estimated 3,500 Aboriginal people living in the region,[3] but increased occupation of land led to conflict with and the displacement of the local Aboriginal people, resulting in the establishment of mission reserves such as Framlingham (twenty-four kilometres northwest of Warrnambool) and Lake Condah (eighty-six kilometres to the northeast) in the 1860s. Early industries revolved around products such as wool, wheat, potatoes, onions, as well as dairy and other cattle, with settlers increasingly occupying land for agriculture and farming. Woollen mills, abattoirs, and cheese and butter factories developed along with these industries during the course of the latter half of the century.

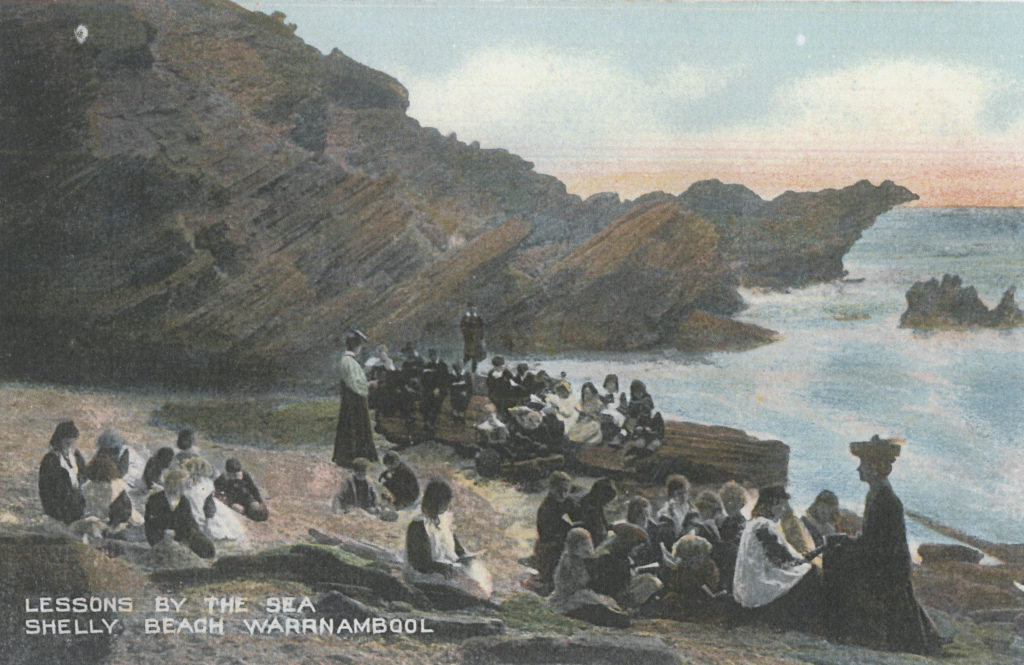

The European town of Warrnambool developed, spurred on by its growing importance as a port – for shipping primary industry products, both to other Australian colonies and farther afield, as well as a stopping point for coastal passenger trade. During the mid to late nineteenth-century it attracted settlers from all over the world, with the majority from Britain, but also a small Chinese population. Its urban infrastructure developed in response, with houses, shops (including branches of Melbourne firms), post office, schools, a mechanics institute, botanic gardens, a racing track, golf and football clubs.

Like much of Australia, Warrnambool experienced a boom in the late 1880s and early 1890s, which included the construction of public edifices such as the Ozone Hotel, the Warrnambool Gallery, and the sea baths, as well as grand private houses. The railway line to Melbourne opened in 1890, which signalled the beginning of the gradual demise of the coastal shipping trade for both goods and passengers, with the port finally closing in 1942.

The early twentieth-century saw the increasing importance of Warrnambool as a regional centre, with further development of industry related to both traditional and new forms of production. The interwar period saw the establishment and further growth of local and international companies, such as Warrnambool Woollen Mills, Warrnambool Cheese and Butter Factory, Nestlé, and Fletcher Jones. The latter perhaps one of the best known of Warrnambool’s locally born companies, which began as a small tailor and hosiery store on Liebig Street in 1924, developing into a major employer throughout much of the twentieth century, with over 1,000 employees at its peak.

Warrnambool’s population is relatively monocultural, with the majority of inhabitants identifying as of Australian or British descent, with only a tiny fraction (0.05%) of the city’s population born overseas, and an even smaller Indigenous Australian population. Small numbers of Warrnambool locals are of continental European descent, including German, Dutch and Italian families, many descended from postwar migrants to the area. Fletcher Jones in particular was a drawcard for such migrants from both Britain and Europe, many of who might be recruited directly from the docks in Melbourne.

Today, farming and associated trades continues to be vital to the Warrnambool economy but other industries are also of central importance, particularly tourism, education, health, energy and construction. The town continues to grow, with new housing developments appearing, and is popular for those migrating from Melbourne or other cities in Australia to retire, take advantage of work opportunities or to experience a ‘sea change’ lifestyle.[4]

References & Further Reading

Australian Geographic Staff, ‘DNA confirms Aboriginal culture one of Earth’s oldest’, Australian Geographic (23 September 2011)

Barry Blake, The Warrnambool Language: A Consolidated Account of the Aboriginal language of the Warrnambool Area of the Western District of Victoria Based on Nineteenth Century Sources (Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, 2003)

Anthony Brady, Sleepy Town of Dennington Awakens to a New Era, The Standard, 16 November 2013, http://www.standard.net.au/story/1911644/sleepy-town-of-dennington-awakens-to-a-new-era/

Robyn Broadbent, Marcelle Cacciattollo, Cathryn Carpenter, ‘The Relocation of Refugees from Melbourne to Regional Victoria: A Comparative Evaluation in Swan Hill and Warrnambool’ (Footscray: Institute for Community, Ethnicity and Policy Alternatives, Victoria University, 2007) https://www.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/Relocation_RefugeeSettleJune07.pdf

Regina Hando, The School on the Hill: Reminiscences on the 75th anniversary of Warrnambool High School (Warrnambool: Warrnambool High School, 1982)

John Lack, ‘Jones, Sir David Fletcher (1895–1977)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/jones-sir-david-fletcher-10638/text18905

Heritage Council Victoria, ‘Victoria’s Post-1940s Migration Heritage: Migration Heritage Study – Thematic History Part 2’ (Melbourne: Heritage Council Victoria, 2011) http://heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/research-projects/responses-to-enquiries/

Hiba Molaeb, ‘Early Childhood Community Profile: City of Warrnambool Aboriginal Community’, (Melbourne: Victorian Government Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010) http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/programs/aboriginal/abprofwarrnambool.pdf

National Museum Australia, ‘Encounters: Revealing Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Objects from the British Museum. Warrnambool region, Victoria’, National Museum Australia http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/encounters/mapping/warrnambool_region

National Museum Australia, ‘Encounters: Indigenous Cultures and Contact History: A Classroom Resource’, National Museum Australia http://www.nma.gov.au/encounters_education/community/warrnambool

Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria, ‘Aboriginal Community Profile Series: Warrnambool Local Government Area’ (Melbourne: Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria Department of Premier and Cabinet, 2014) http://www.maggolee.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/LGA-Profile-Final-Warrnambool.pdf

Profile.id, Warrnambool City Community Profile

Victorian Council of Social Service, ‘Background information regarding Victoria’s Indigenous communities’ (Melbourne: Victorian Council of Social Service, 2006) http://www.vcoss.org.au/documents/VCOSS%20docs/Indigenous/REP%20-%20Victoria’s%20Indigenous%20Communities_CA_Oct06.pdf

Warrnambool City Council, ‘The Point Ritchie Story’, Moyjil Point Ritchie (2016) http://www.moyjil.com.au/point-ritchie-story

Warrnambool Primary School, Warrnambool Primary School 1743: 100+25 Years (Warrnambool: Warrnambool Primary School, 2001)

Jessica K Weir, The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story (Canberra: Native Title Research Unit, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2009)

Footnotes

[1] Warrnambool City Council, ‘The Point Ritchie Story’, Moyjil Point Ritchie (2016) http://www.moyjil.com.au/point-ritchie-story; Gunditjmara is the term for the wider Aboriginal population of far southwestern Victoria, stretching into southeast South Australia: Jessica K Weir, The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story (Canberra: Native Title Research Unit, the Australian Institute of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2009)

http://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/products/monograph/weir-2009-gunditjmara-land-justice-story.pdf. New genome sequencing indicates that the ancestors of Australia’s Indigenous people probably only left Africa 75,000 years ago: Australian Geographic Staff, ‘DNA confirms Aboriginal culture one of Earth’s oldest’, Australian Geographic (23 September 2011)

[2] ‘Visit Wonderful Warrnambool’, Visit Warrnambool, http://visitwarrnambool.com.au/visitor-information/about-warnambool/#.VzFm6mZ4gpk

[3] ‘History of Warrnambool: Brief History of Warrnambool’, Warrnambool & District Historical Society, http://www.warrnamboolhistory.org.au/warrnambool-history/history/; Weir, The Gunditjmara Land Justice Story; Warrnambool Primary School, Warrnambool Primary School 1743: 100+25 Years (Warrnambool: Warrnambool Primary School, 2001), 30.

[4] Almost 6,000 people moved to Warrnambool in 2006–2007, the majority from other parts of Victoria: Profile.id, ‘Warrnambool City: Migration Summary’, Profile.id, http://profile.id.com.au/warrnambool/migration; Warrnambool City Council, ‘City Information’, Warrnambool City Council (2016) https://www.warrnambool.vic.gov.au/city-information